Back when Jerry Brown was dating Linda Ronstadt, I was a freshman English major at Loyola College of Baltimore. I’d just signed off a container ship where I handled lines, chipped paint and read David Copperfield to figure out how stories were “made.” Ashore, I began tugging at the veil of literature for clues.

One of the first books I was assigned in the fall of ’76 was My Antonia by Willa Cather. I promptly ignored it. At 18, a pioneer story from the 19th century Nebraska prairie was not my idea of a good time.

Somehow – turning in papers soaked with what the novelist Tim O’Brien calls “spiced-up hogwash” – I passed. And soon landed a clerk’s job in the Baltimore Sun circulation department, my first rung toward the feast (succulent entrees side-by-side with lustrous but empty calories) of the written word.

I’ve always collected books. A new set of the World Book Encyclopedia in the 2nd grade (with the transparent, overlapping pages showing how the innards of a frog connect) is among my all-time favorite gifts.

For me, and many thousands like me, something to read (preferably not trash) must always be close at hand. Especially if you’re stuck somewhere.

Over the holidays about a decade ago, I picked up my daughter Amelia (whom I forced to read Travels With Charley when she was a kid) at the airport. When we got to my Toyota pick-up there was no room for her luggage, books fore to aft. Behind my back, Amelia filmed the moment without telling me, watching as I wrestled with everything from the alchemy of Roberto Bolano, church cookbooks and advice about children who wet the bed.

As I tossed titles around like sacks of flour to wedge in her bags, she asked, “Where did all of these books come from?”

“People moved and people died.”

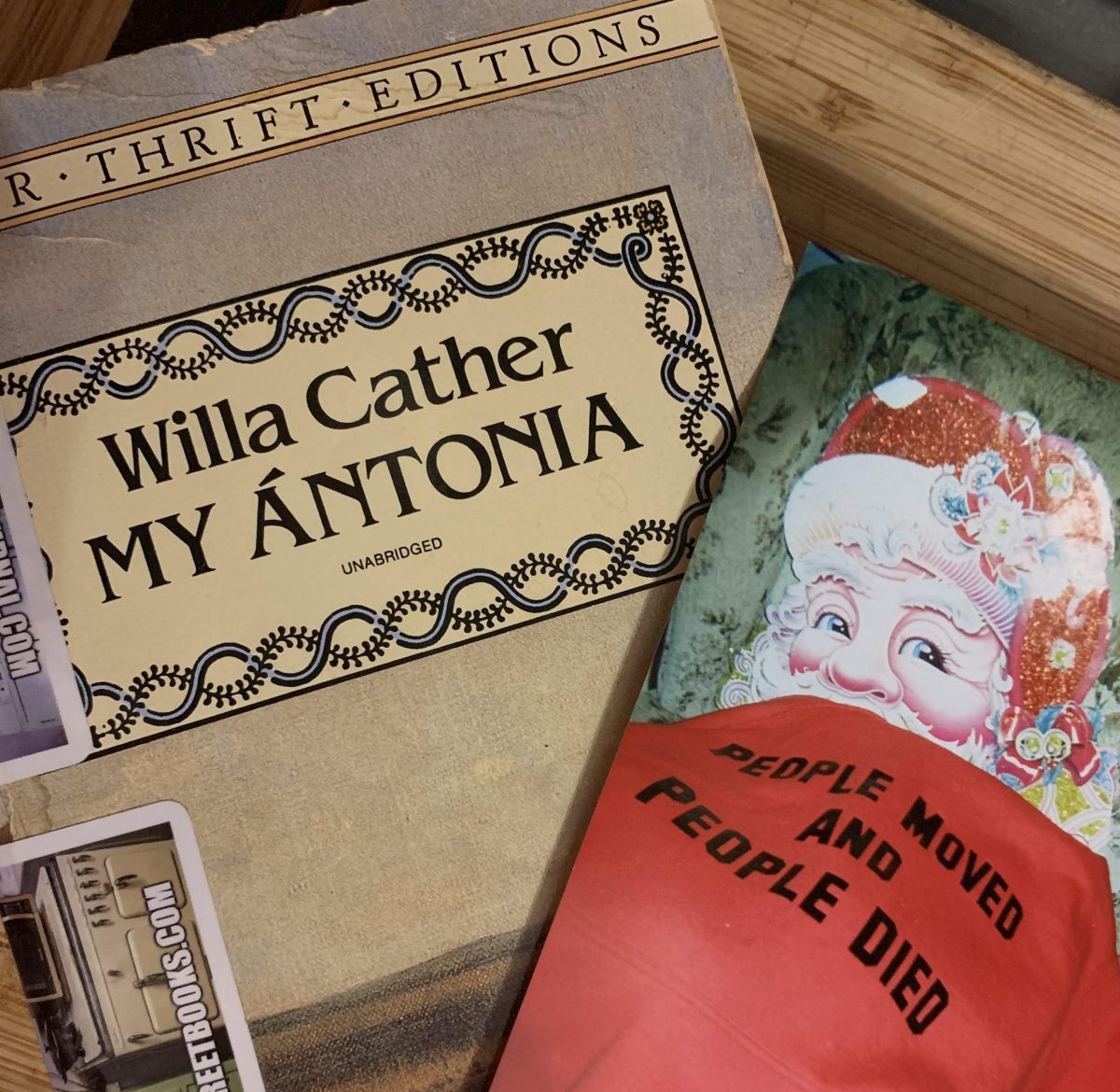

That Christmas, she gave me a bright red hoodie emblazoned in black: “PEOPLE MOVED AND PEOPLE DIED.” It’s not something you can wear to midnight Mass.

I now have a Corolla hatchback so stuffed with books that my four seater has become a two seater. And that brings me a half-century down the road from absconding with an English degree from a Jesuit university, as I stand in a Glen Burnie parking lot, about to get what’s left of my hair shorn to the scalp and needing something to read as I wait my turn.

Pop the hatch and there it is: My Antonia, a beat-up, broken spine edition from Dover Thrift, two bucks new in 1994!

How did it wind up there? People moved, people died and those who were left behind called their friendly neighborhood writer freak to come and get it.

Not one in 10,000 writers at any rung on the ladder can pull a rabbit like this passage out of their typewriter.

“As I looked about me I felt that the grass was the country, as the water is the sea. The red of the grass made all the great prairie the color of wine-stains, or of certain seaweeds when they are first washed up…there was so much motion in it; the whole country seemed, somehow, to be running.”

I was hooked like a Chesapeake Bay rockfish. And dove deep into all things Cather (1873-1947), highlighted by a road trip in May to her childhood home in Red Cloud, Nebraska. I deliberately put off finishing Antonia until arriving.

[And in my haste bypassed nearby Hastings, mentioned in the book several times and renowned as the birthplace of Kool-Aid.]

I stayed in an apartment at the old Red Cloud opera house (now headquarters for the thriving Willa Cather Foundation) where, in 1890, Willa delivered her high school graduation speech.

Across the street, the post office (the smallest of American towns have one, even if it’s a double-wide trailer), a saloon with a good offering of pork and beef and a coin laundry where, on the community bulletin board, was a request for birthday cards to be sent to a recently rescued dog. I happily did so, but the pooch didn’t write back.

The population of Red Cloud hovers around 950, many of them employed in health care and agriculture. Men walk around with pliers on their belts to twist ranch wire the way cops carry guns.

It was close to 2,500 when nine-year-old Cather and her family arrived from Virginia and Nebraska had been a state for about a dozen years. There, she befriended a Bohemian girl named Annie Pavelka upon whom Antonia Shimerda was so closely modeled as to be a biography.

Cather loved Annie and I fell for Antonia and her spirit while enduring hardships from which Jim Burden (narrator and fictional stand-in for Willa) and his family were exempt. The Shimerdas lived in a dugout cave, they arrived without being able to “speak enough English to ask for advice…” – and despaired the suicide of Antonia’s delicate, beloved father whose heart ached to play the violin for his friends back in the old country.

Visiting the landmarks was nice, among them the train depot where the Cather family was delivered more than 140 years ago and the old school newspaper office of the Red Cloud Chief where Cather published her earliest stories.

It was not on the front steps of Willa’s childhood home on Cedar Street or even the 600-acre slice of remaining Nebraska prairie that carries her name where I became entranced. I was seduced on the page, way out in the universe of ink and paper where certain souls are immortal and many others are dead on the page.

All because I needed something to read while waiting for my name to be called at the barbershop.

Revisiting classics

Young people have been avoiding reading assignments since the days of Gutenberg. The ranks of those who revisit the texts decades later – finding pleasure and enlightenment — are much smaller.

In a casual canvas of friends and strangers, many of them avid readers, the usual parade of jilted works rolled in: Moby Dick, Don Quixote, Ullyses and its progenitor, The Odyssey. Thomas Hardy came up often.

For Grace Bigelow, back when Nixon was president and she was Muffie Doyle at Roland Park Country School, it was Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles that proved unwelcome in the 9th grade. She found it “a slog.”

“I gave up several times,” said Bigelow, now living in Hamilton. “Only to become slightly obsessed with it in my early thirties.”

Maybe it’s like Brussels sprouts or lima beans. A 13-year-old’s sullen trudge across the dinner plate often becomes enticing in early middle age, perhaps because they’ve learned the hard way not to take food for granted.

As an adult, said Bigelow, “I went on a kick reading the classics I avoided in school, discovering all the things I’d missed because of youth and inexperience. Wow! Tess was so overwhelmingly sad and frustrating, so much juicer and tragic than I expected – misogyny, class distinctions and religious zealotry. I had no clue!”

Here is perhaps the greatest tribute a writer can hope to earn, an honor that generally occurs without notice. It comes from Baltimore artist Ann Feild, perhaps best known for her front page cartoons of the Oriole bird in The Sun.

“My mother had no formal education beyond high school but was a lifelong lover of literature,” said Feild of her mom, the former Rebecca Jane Stromberg. “She gave me many books to stir my imagination … by Tennyson, Thomas Mann, Barbara Tuchman. And My Antonia.”

Cather was Rebecca’s favorite, standing a notch above other cherished authors like Edith Wharton. On the day she died, remembered Ann, her mother was “clear minded and in good spirits’ as they discussed Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop over tea and toasted raisin bread. It was late January 2000, a hint of snow was in the air.

That night, Mrs. Feild died in her sleep, a rosary on her nightstand and a certain book among her final thoughts.

“When my siblings and I visited the house the next day, I noticed that Cather’s novel Song of the Lark had been pulled from the living room bookshelf.”

Is that not a Nobel of sorts?

Rafael Alvarez has made pilgrimages to the graves and hometowns of many authors over the years, including Thomas Wolfe, William Saroyan, Sherwood Anderson and Marcel Proust. He can be reached via orlo.leini@gmail.com

Rafael- wow, thank you. Just thank you.

When I think of all the great books that were wasted on me and my classmates (Although I actually loved My Antonia), I wonder why the schools bothered. It probably looked real good, somewhere, to have “Our students read Finnegan’s Wake!” Someone, like Oprah, should start a book club for people who revisit their high school classics